In this article, I am going to create a distributed ETL pipeline for extracting, transforming, and storing comments from HackerNews.

Background

The general steps of my ETL process are going to be:

RSS Feed –> Kafka –> PySpark –> MySQL DB

I will be initially sending new comments to Kafka for a few reasons:

- It is a fault tolerant method for streaming data

- It works fluidly with Pyspark, which I will be using at the transformation step of the ETL pipeline

I’m going to be using a local MySQL database as the final warehouse for storing the transformed data.

To start, we need to create a means of collecting new comments from Hacker News, as well as a Kafka server for publishing these comments. I’ve already created a Kafka topic titled hncomments with one partition. To collect the data, I’m going to be using the feedparser library.

Building the RSS Feed Parser

The HNFeed class will serve as the main class for pulling data from the Hacker News RSS feed and sending it to the Kafka server. We first instantiate the class by providing the link to the RSS feed, and constructing a producer to send comments to Kafka.

class HNFeed:

def __init__(self):

self.rss_link = r'https://hnrss.org/newcomments'

self.last_modified = None

self.producer = KafkaProducer(bootstrap_servers = 'localhost:9092',

key_serializer = lambda k: bytes(k, encoding = 'utf-8'),

value_serializer = lambda v: bytes(v, encoding = 'utf-8'))

As we’ll see below, we need the last_modified parameter to tell the parser when the last call was made, so that we don’t make duplicate calls and put too much stress on the RSS server.

To get new comments, we can write the following function:

def get_data(self):

self.feed = feedparser.parse(self.rss_link, modified = self.last_modified)

self.last_modified = self.feed.modified

if len(self.feed.entries) > 0:

print('Found {} new entries after {}.'.format(len(self.feed.entries), self.last_modified))

get_data will make a call to the RSS feed, and reset the last_modified variable to the time of the latest call. Then the function will check if any new comments have been produced since the last call.

Now we can write a function for sending data to the Kafka server.

def send_data(self):

for entry in self.feed.entries:

id_ = entry['id'].split('=')[1]

text = entry['summary']

self.producer.send(topic = 'hncomments',

key = id_,

value = text)

The send_data function simply grabs all of the new entries, and takes two pieces of information from each, the unique ID of the comment, and the full text of the comment. Notice at the end of the function, where we are sending the Kafka

Now we can combine these two functions together to create a stream of comments from Hacker News:

def run(self):

while True:

self.get_data()

self.send_data()

time.sleep(10)

Now we can run the following lines to start the parser:

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = HNFeed()

parser.run()

and after running the program for a while we’ll get an output like this, where each line tells us how many new comments were found by the parser:

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 01:20:39 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 01:23:33 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 01:28:46 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 01:29:19 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 01:34:20 GMT.

We include time.sleep(10) not to overdo it on API calls, so that I don’t get banned :() .

First, we will instantiate a new SQL database hncomments, then create the table comments to hold new comments and their respective IDs.

Creating a PySpark Transformation Pipeline

Now that we’ve created a service for scraping and storing the raw comments, we can start transforming and extracting information.

We first need to setup our Spark environment, and let the program know that we’ll need some dependencies for integrated Kafka streaming.

First we import some libraries for creating streaming Spark applications, and then tell the program that we need the required java dependency for streaming Kafka applications.

from pyspark.sql import SparkSession

from pyspark import SparkConf, SparkContext

from pyspark.streaming.kafka import KafkaUtils

from pyspark.streaming import StreamingContext

os.environ['PYSPARK_SUBMIT_ARGS'] = '--packages org.apache.spark:spark-streaming-kafka-0-8-assembly_2.11:2.4.6, pyspark-shell'

Then we can setup our SparkContext and StreamingContext variables:

sc = SparkContext(appName = 'StreamingKafka')

sc.setLogLevel('WARN')

ssc = StreamingContext(sc, 5)

We’re setting the batch duration for our streaming context to 5 seconds, meaning it will ping our source Kafka server for new data every 5 seconds.

And now we can instantiate our Kafka stream with the following lines:

kafkaStream = KafkaUtils.createStream(ssc = ssc,

zkQuorum = 'localhost:2181',

groupId = 'hn-streaming',

topics = {'hncomments': 1})

Here, we’re connecting to our local zookeeper server on our HackerNews topic (beforehand we titled this topic hncomments).

At this point, we are able to read the stream of Kafka messages in their raw form, but it will be easier down the line to export the data to our SQL warehouse. To convert each batch of streaming data into a dataframe, we can use the following code:

from pyspark.sql import Row

def getSparkSessionInstance(sparkConf):

if ("sparkSessionSingletonInscance" not in globals()):

globals()['sparkSessionSingletonInstance'] = SparkSession \

.builder \

.config(conf = sparkConf) \

.getOrCreate()

return globals()["sparkSessionSingletonInstance"]

The official PySpark documentation describes this approach as “creating a lazily instantiated instance of a SparkSession”. If you wanted to, you could also register the resulting dataframe to a temporary SQL table, but, we don’t need this functionality right now.

Now we can write our function for transforming each batch of text data. I wrote a simple function here that normalizes each comment to remove html tags, remove numbers, and lower the characters.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import re

def clean(document):

document = BeautifulSoup(document, 'lxml').get_text()

document = re.sub(r'[0-9]', '', document)

return document.lower()

Writing to the Warehouse

The final step before putting the Transformation step together is creating a function to write the transformed comments to our data warehouse, in this case our SQL table.

def writetodb(df):

url = 'jdbc:mysql://localhost/hncomments'

driver = 'com.mysql.cj.jdbc.Driver'

dbtable = 'comments'

user = 'root'

password = 'sqlpassword'

df.write.format('jdbc').options(url = url,

driver = driver,

dbtable = dbtable,

user = user,

password = password) \

.mode('append') \

.save()

All we’re doing here is locating our local MySQL database, titled hncomments (not to be confused with our Kafka topic of the same name, sorry for the confusion), and writing our resulting dataframe to the comments table.

We created the MySQL database yet, We’ll do that in a second. But first we can put our Transformation step all together with the following function:

def process(time, rdd):

if not rdd.isEmpty():

spark = getSparkSessionInstance(rdd.context.getConf())

clean_rdd = rdd.map(lambda x: (x[0], clean(x[1])))

rowRdd = clean_rdd.map(lambda x: Row(comment_id = x[0], comment = x[1]))

df = spark.createDataFrame(rowRdd)

writetodb(df)

df.show()

For each new batch of data, process will create a new Spark Instance, map our clean function to each row, and convert the transformed RDD to a DataFrame. Finally, the function appends the transformed data to our comments table in the MySQL database.

We finally have to tell the SparkApplication to perform the process function for each new batch, and so we use the following command:

kafkaStream.foreachRDD(process)

and then we start the streaming process:

ssc.start()

ssc.awaitTermination()

But before we run this line, we have to create the database where our transformed text data will be stored.

CREATE DATABASE hncomments;

USE hncomments;

CREATE TABLE comments(

id INT NOT NULL AUTO_INCREMENT,

comment TEXT,

comment_id TEXT,

PRIMARY KEY (id));

Here we have just created a simple database with the comments table, which has the same schema as the resulting DataFrames from our transformation step.

Now we can finally run the entire ETL pipeline and see what happens:

We first capture a few more entries from our RSS feed, as shown by the output from our HNFeed output:

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:04:41 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:07:27 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:13:31 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:18:40 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:21:18 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:28:32 GMT.

Found 20 new entries after Thu, 31 Dec 2020 05:29:35 GMT.

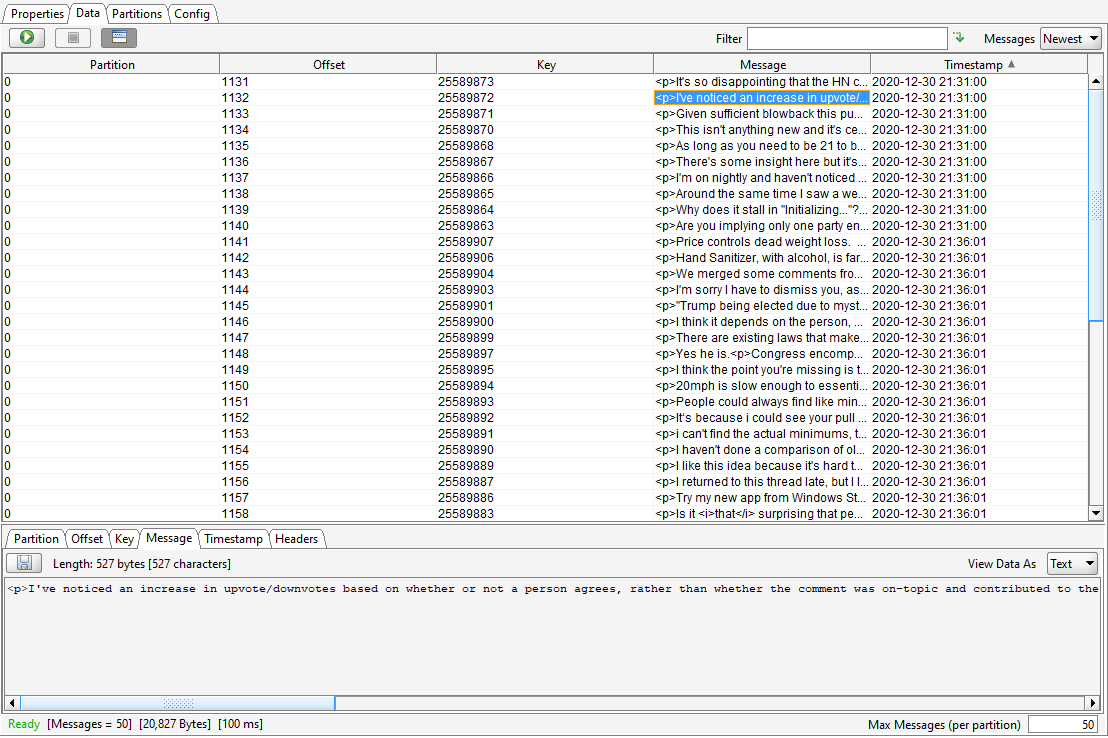

The collected entries are then immediately ingested by the Kafka server. For demonstration, here is a capture of the newest entries in the feed, shown in the Kafka Tool GUI .

The Kafka server then sends the new batch of data to the PySpark step, which processes the batch and returns a dataframe like this:

+--------------------+----------+

| comment|comment_id|

+--------------------+----------+

|where do you live...| 25589966|

|how many people h...| 25589963|

|i mostly emailed ...| 25589962|

|the problem is co...| 25589961|

|to be pedantic, y...| 25589960|

|i know this is in...| 25589959|

|i think there's t...| 25589958|

|> cross platform ...| 25589957|

|i don't know what...| 25589955|

|i didn't see your...| 25589953|

|in a vacuum maybe...| 25589951|

|anecdotally, i al...| 25589950|

|it's over half of...| 25589949|

|thanks for the co...| 25589948|

|we have a good st...| 25589947|

|where are all the...| 25589946|

|have you got a so...| 25589944|

|it's not a price ...| 25589943|

|indeed. arguing t...| 25589942|

|this is what i've...| 25589941|

+--------------------+----------+

And once the data has been transformed, it is stored in our data warehouse, the SQL server. We can view the previously transformed data with the following query:

SELECT SUBSTRING(comment,1,20) AS preview, comment_id FROM comments LIMIT 10;

Which returns a table similar to our Spark output:

+----------------------+------------+

| preview | comment_id |

+----------------------+------------+

| in my brother and i | 25586084 |

| google's fundamental | 25572365 |

| >i have an extra day | 25584402 |

| i worked at a compan | 25572046 |

| it's probably confir | 25571254 |

| i switched to a -day | 25584019 |

| i have noticed that | 25571163 |

| there's a somewhat p | 25582174 |

| "forced labor"it's s | 25570687 |

| 'he tells us: "event | 25578836 |

+----------------------+------------+

10 rows in set (0.0008 sec)

Conclusion

This was a simple ETL pipeline constructed on my local machine, and could eventually be expanded to span more partitions to be more fault tolerant. The current application is not totally immune to failure, since there is only one worker for the Spark transformation step, meaning a CPU failure would lead to loss of the current batch of data collected from the RSS feed.

A better, production-level service would account for this by allocating more workers to the Spark process, but this was just for demonstration purposes. A similar point could be made for the Kafka server, which also only spans one partition.

Likewise, our data warehouse is stored locally for this case, and is also not immune to system failure. In the future, a much more secure approach would be to store the transformed data in a distributed data warehouse, like Amazon RedShift.